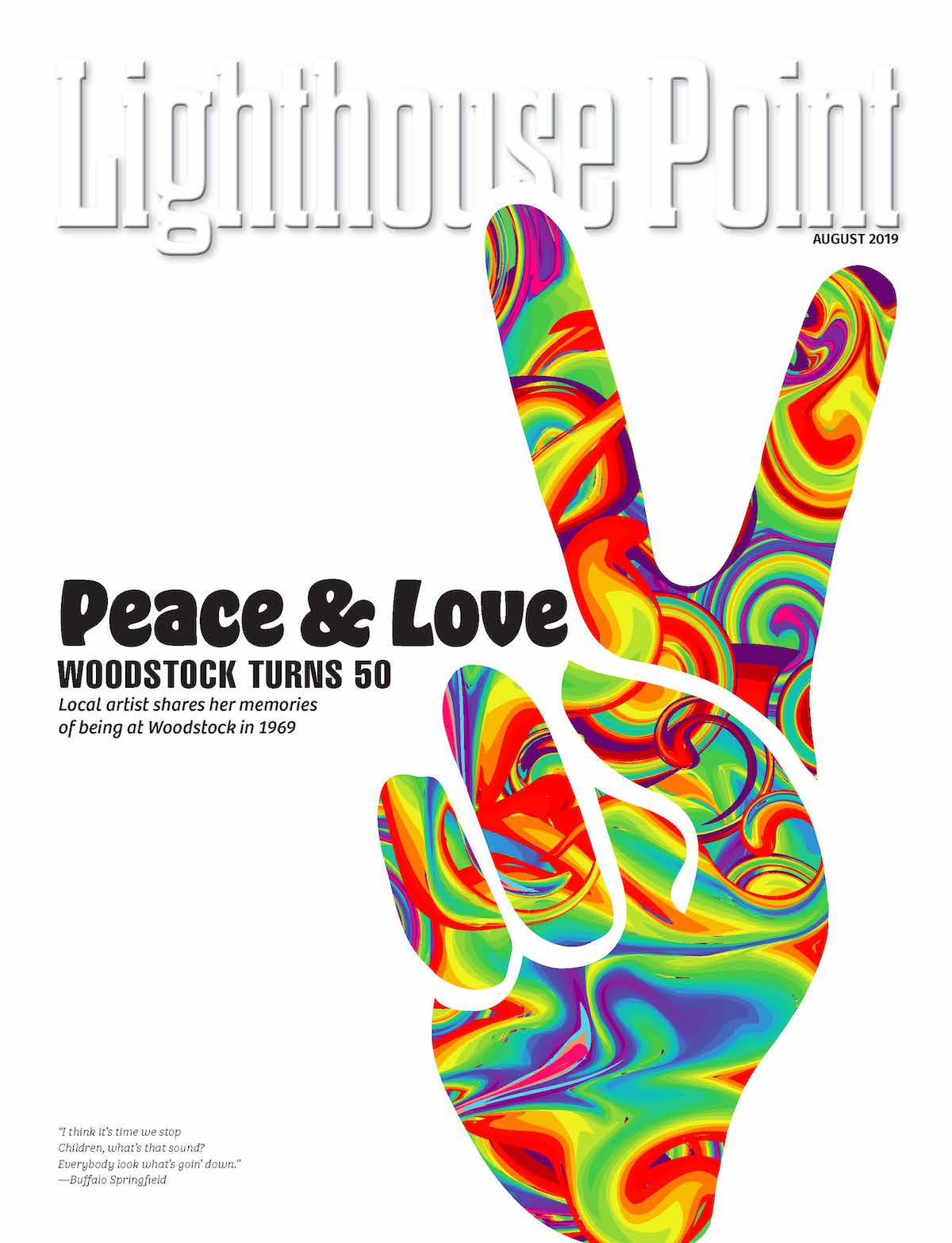

It has been 50 years since the famed summer of ’69. That July, roughly 600 million people watched Neil Armstrong take his first steps on the moon. In August, according to some estimates, roughly a million people flocked to Bethel, NY to attend Woodstock, the iconic three day music festival which gave attention and momentum to the anti-establishment, 1960s counterculture. That same summer, anti-war protests cropped up across the country, leading to the November 15 protest in Washington, D.C. believed to be the largest anti-war protest in U.S. history. And, in June, the Stonewall Riots sparked the beginnings of the gay rights movement. It was indeed a historic summer — one to forever be remembered and recounted by nostalgic Baby Boomers. In celebration of Woodstock’s 50 year anniversary, we commemorate that summer by sharing the story of Mimi Botscheller, a local artist who was at Woodstock before the crowds arrived.

—————————–

Mimi Botshceller remembers when the mobs of youth arrived at the Woodstock Music Festival, breaching the fence and flooding into the alfalfa field at Max Yasgur’s dairy farm in Bethel, NY in August 1969. Days before, that very field had been empty, buzzing with energy as crews helped set up the stage, string the lights and hang large canvas tarps over telephone poles to create a backstage for the coming talent.

She had stood, looking out over the empty field as the sound system was installed and the first test conducted. The first tunes to reverberate through the speakers were the twangy guitars and melodic lyrics of Crosby, Stills and Nash, “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.”

“It’s getting to the point…” Mimi sings, dancing in her chair, recounting the moment and soaking in the feeling as if she were still there.

“It sounded perfect on that sound system,” she tells me over coffee at Chez Cafe in Pompano Beach. “It was really a good sound system. Those people knew what they were doing with the sound. Everybody cheered. And from that time on they played music the whole time while we were working.”

Mimi had road tripped to Bethel in her parents car (a car she would later be forced to abandon in the field, blocked by an ever-expanding lot of other cars) from New York City to work at the concert with her boyfriend and friends, whom were ushers and concert promoters for the legendary Fillmore East — a concert venue in the Lower East Side known as the “The Church of Rock and Roll.”

Fillmore East, a companion to the famous Fillmore Auditorium and Fillmore West in San Francisco, attracted the biggest acts in Rock and Roll. Mimi had spent the summer of ’69 — her last summer before college — with a girlfriend and the Fillmore East crew trekking to concerts across the country and, when in New York, selling candy at concert intermissions.

At Woodstock, she was supposed to work the talent tent, serving drinks and food to the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. That plan, of course, went out the window when what was supposed to be a well-promoted, but controlled and ticketed concert for a crowd of about 50,000, quickly spiraled into a free show for, according to some estimates, a million people.

While Mimi and the crews had worked diligently to erect the venue in time, they weren’t quick enough for the crowds who arrived early. Neither the fences, nor the ticket booths, nor the bathrooms had been finished when the first waves came streaming in.

First to arrive, Mimi remembers, were the “Hog Farmers” — a group of nomadic hippies from a commune in California who rolled up in psychedelic, multi-colored school buses. Soon after lines of cars paraded in, creating a mass of rows, surrounding the venue, essentially turning the stage into an island at the center of a sea of cars. Some highways and local roads came to a complete standstill as hippies with long hair and flower children in flowing skirts abandoned their cars in the road. Delivery trucks were blocked off from bringing in food, water and supplies. Even the talent couldn’t get in by ground.

“They had to be helicoptered in,” Mimi recalled, laughing.

What had once been an empty field, now became the set for arguably the most remembered, debaucherous and iconic concerts in American history — a symbol for the anti-establishment, 1960s counterculture movement.

In the past 50 years since Woodstock, the concert has taken on near-mythical proportions. Rolling Stone listed it as number 19 of the 50 Moments That Changed the History of Rock and Roll. Not only was the three-day music lineup one of the most well-stacked of the era (with 32 legendary acts including Jimi Hendrix; Santana; Janis Joplin; Richie Havens; Creedence Clearwater Revival; the Grateful Dead; Sly and the Family Stone; The Who; Jefferson Airplace and The Band), the festival represented a moment in time when youth came together in spite of challenging conditions — both at the concert itself (without water, food, places to sleep or sanitary conditions), and culturally, (in the face of the Vietnam War and wake of the Civil Rights movement). Woodstock was an opportunity to stand for a spirit of love and community, to push back against the forces of hatred, violence and war.

The massive Vietnam protests that had been happening across the country that summer gave momentum to Woodstock, Mimi said. She had seen the streets of New York City shut down by protesters, and would later see the protests on Washington D.C. reach crowds of roughly a half a million.

“It was all a buildup of all of those activities. And then with the music backing it — saying this is not what we want. We want peace, we want love, we don’t want war, was a statement,” she said. “Woodstock was its own form of protest.”

Or as one writer and Woodstock attendee, Susan Reynolds, wrote so eloquently in her 2011 essay: “The music bonded us; our humanity engulfed us; our sense of global significance embodied and empowered us as a swaggering band of youthful dreamers. The counterculture had a visual…For those who yearn to hear our personal stories, it seems to be a desire to know, on some level, how that felt.”

For Mimi personally, Woodstock and the summer of ’69 made an indelible impression on her soul. The experience, she said, most likely altered her trajectory as a longtime artist, lover of music and art teacher, empowering youth to claim their own creative and political voices. She was a teacher at the The Art Institute of Fort Lauderdale for many years. One of her students, Dennis Friel, is widely known locally in Pompano Beach as the muralist whose work now adorns the new Atlantic Boulevard Bridge.

Mimi’s own work still maintains a rather hippie aesthetic — abstract, spiritual, bright and ethereal. Flowers are a regular subject, as are stars and nature. She has recently gravitated to photography and mixed media work, often with a surrealist undercurrent.

Writing, too, may be on her horizon as she is a woman with many stories; such as meeting Salvador Dalí when she was 19, painting concert backdrops for the Marley Family, photographing Led Zeppelin’s very first U.S. show and, as a child, training in ballet with Russian defectors in New York City. Having coffee with Mimi is an exciting ride, and her storied life is evident in her layered and captivating artwork.

She is an artist representative sitting on the Public Art Committee for Pompano Beach and has showcased her work multiple times at Bailey Contemporary Arts. Her son is a musician currently recording and living in Los Angeles, and her husband, Scott Sherman, works in advertising and is an accomplished guitarist playing in local band, The Wolfepak Band.

Woodstock will forever remain a treasured memory — a turning point for both Mimi, and our nation.