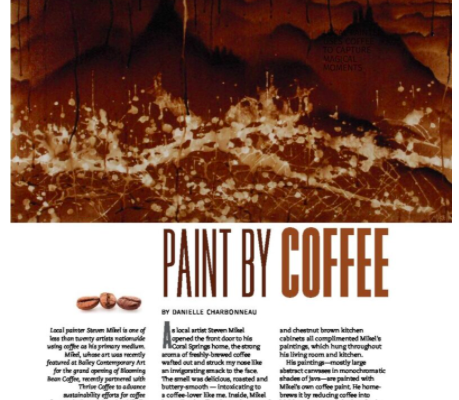

A young man in the juvenile justice system. Ross said his striped prison scrubs have since been prohibited in the system for their similarity to slave history. Courtesy of Richard Ross and Hammer Muesum

By Danielle Charbonneau

An 11-year-old asian boy sits cross-legged on a thin cot wearing pale blue jail scrubs. His shaggy black hair sweeps across his forehead, his chin down, obscuring his face from view. He looks fragile and tiny. Yet he’s confined to a locked cell.

A 15 -year-old girl in an orange jumpsuit sits alone in the corner of a concrete box. A long thin rectangle of white light streams in from the window, bouncing off the reflective surface of her stainless steel toilet. Its a shiny concrete box; sterile and isolating.

These were just two of about 50 images projected on screen at the Billy Wilder Theater at UCLA’s Hammer Museum last night during a discussion with researcher and photographer Richard Ross. Ross has spent ten years traveling the country and world, photographing juveniles in detention facilities. Ross recently released Girls in Justice, a follow-up body of work to his first series, Juvenile in Justice.

Ross’ photographs are aesthetically stunning (Ross has a background in architectural photography), but the imagery is undeniably heart breaking. So are the statistics: approximately 70,000 teenagers and children are in lockdown in the United States nightly; about 4,500 new kids are committed to the system every day. Two-thirds of the males and three-quarters of the females meet the criteria for psychiatric disorders. And the cost is exorbitant: It costs between $66,000 and $88,000 to house a juvenile in the system for six to nine months.

Ross knows however, that statistics can be as sterile and impersonal as the concrete cells he photographs.

“You have to go beyond the horrific statistics and convince people that there are lives at stake,” Ross said.

Ross’s goal is to re-humanize juveniles in the system. He says he wants his viewers to be able to say “that’s my kid.” Ross frequently obscures the children’s faces to achieve this goal. The sense of isolation in Ross’ photographs is chilling.

“These are the loneliest kids on the planet,” said Ross.

The individual stories of each juvenile varies child to child, but most have common threads: traumatic backgrounds, poverty and violent environments. Ross said close to 100 percent of girls in the system have sexual abuse and/or rape in their histories. Four out of five females were running away (often from abuse) when they were picked up for the crime that landed them inside.

“This [the system] is not a place to heal, or a place to understand,” said Peter Sellars, a professor in UCLA’s department of world arts and dance who was co-moderating the discussion. “It [the system] doesn’t explore cause.”

Two audience members, both young African American males in their early 20s, took the mic during the Q & A after the presentation to share their appreciation and personal connection to Ross’ work. Both young men were visibly shaken and emotionally charged by Ross’ photos. They shared harrowing tales of having been locked up for crimes they committed as adolescents.

“I got straight As in school. But the environment we grew up in sends negativity into your life. There’s nothing positive,” one shared. “My time inside changed me.”

The young man’s story illustrated a point Sellars made earlier in the evening: that kids lives are irreversibly altered based on a “bad day” or mistakes made during the impressionable era of adolescence.

Ross commended both of the young men for having the courage to speak up.

“The fact that you are even here is remarkable,” responded Ross.

The system is tremendously emotionally scarring.

“It fucks kids up,” Ross said, stating it more bluntly.

Both Sellars and Ross have been strong supporters of art with social purpose. The conversation was part of Sellars’ budding project, the Boethius Initiative. Sellars’ vision for the initiative is an institute that will bring together scholars, artists, journalists and social workers for months, or years, at a time to create multi-layered work that enlightens and advocates for social issues.

Most recently, Sellars has focused on issues surrounding the justice system

“Prisons run the politics in this state in a very visceral way,” Sellars said. “Our punitive overreaction is so destructive.”

Ross agreed. His aim, he said, is not so much to make the system more rehabilitative, but rather to keep kids out of the system in the first place.

You can view a sample of Ross’ work at http://www.juvenile-in-justice.com/shop/girls-in-justice