Crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge into downtown Selma is like entering a time machine. Once you cross it, you’ll find 1950s Ford pickups, factories and a languorous main street. The homes outside downtown feel antebellum with wrap around porches, plantation columns, rocking chairs and swaying wide oak trees.

Beyond the exterior, you can sense a residue of old ideas. As writer-journalist David Holthouse so poetically puts it: “Selma feels like entering a time warp in which the past maintains such a stranglehold on the present that a breeze off the Alabama River seems to carry a whiff of tear gas or the distant crack of a slave master’s whip.”

The bridge itself carries old connotations. Though Common praised it at the 87th annual Academy Awards for its place in Civil Rights history, calling it a symbol of hope, “welded with compassion,” the bridge is named after Edmund Pettus, a former confederate general and Grand Dragon of Alabama’s Ku Klux Klan.

On the far side of the bridge there is a billboard featuring another Confederate General, Nathan Bedford Forrest, the widely recognized founder of the Ku Klux Klan. Under Forrest is the caption, “Keep the Skeer (Scare) on Em,’” a phrase used by the KKK to encourage white supremacist fear tactics. Friends of Forrest, a neo-Confederate group that vocally advocates racial segregation, sponsored the billboard. While the sign advertises history tours, its subtext is hard to miss.

Directly across the highway from that billboard, however, is another that carries a different tune. It shows a picture of a fully integrated, diverse group of smiling young people. Above their heads is the phrase, “Honor the Past. Build the Future.” The billboard literally, and figuratively, opposes the other. It was sponsored by a non-profit called the Freedom Foundation. The foundation is an umbrella organization for a number of programs that all aim to fight old ideologies by investing in Selma’s youth.

While Selma is known for its place in Civil Rights history, it is still littered with symbols of racism, layered with systems of oppression, fractured by segregation and burdened by social issues like poverty and crime.

The foundation subscribes to the idea that it takes the energy of young people, and the wisdom of the old, for activism to be impactful. The foundation has a youth theater company (Random Acts of Theater), a youth mentoring and job training program (The Freedom Cafe), an Alternative Spring Break program and a student activist group called Students UNITE. The foundation also offers nonviolence training and believes, like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., that it takes agape (unconditional) love and confrontation to bring about lasting change.

The group has frequently partnered with 1960s foot soldiers like John Lewis, Sheyanne Webb and Lynda Lowery, and has drawn inspiration from the Civil Rights Movement. Students UNITE in particular, is partially modeled after the Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The foundation, in a sense, is a new wave of King’s movement. I shadowed the Foundation in March while visiting my mom and stepdad who volunteer with the organization.

Town in a Time Warp

I arrived the week after Jubilee, the annual festival that celebrates the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s historic march from Selma to Montgomery that led to the passing of the Voting Rights Act. The 2005 Jubilee was the annual festival’s largest yet. It brought a crowd of more than 40,000 people to the small southern town, among them President Obama and Oprah. By the time I got to Selma, however, the crowds had dissipated and the town had returned to its sauntering southern pace.

Upon arriving, I was immediately confronted with the town’s hateful history; first by the Friends of Forrest billboard, then by a small confederate reenactment festival. In a neighborhood just outside downtown, white women in hoop-skirt Victorian gowns, ornate jewelry and coiffed hair ambled into historic homes. Costumed Confederate soldiers play-battled in the leaves, fighting the North to keep Selma a slave-owning state.

The festival, I thought, had odd timing (a week after celebrating Civil Rights), but the locals seemed blissfully oblivious. Some in Selma have a genuine pride in their town’s confederate history. Others use it to disguise old ideology (i.e. antebellum and Jim Crow-era nostalgia).

I felt yet another air of that nostalgia my second day in Selma. As I meandered down Broad Street I passed a group of African American construction workers out for a smoke break. I stopped and asked if I could join them, to which one replied: “You’re not from around here, are you?”

“How can you tell?” I asked.

“Because you’re conversing with us,” he said, chuckling.

“People don’t converse with you?” I asked.

To which, he replied, “no one white like you.”

At that exact moment, a group of luxuriously dressed Southern belles with bright lipstick and rouged cheeks walked toward us putting their heads down in a condescending manner before circling around us with obvious distance. Perhaps they had disdain for cigarettes, but it felt more spiteful than that.

The billboard, confederate reenactment ceremony and exchange with the southern women were just my first few experiences in Selma. I know, however, that the town’s racial inequalities and social issues run far deeper than that.

Dallas County, where Selma is located, is ranked the poorest county in Alabama. In January, Selma had an unemployment rate of 10.3 percent according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (almost double the national average at 5.5 percent). 42 percent of Selma’s families live below the poverty line, according to the Census Bureau. Violent crime is five times higher than in any other Alabama town.

The Selma country club has yet to admit a non-white member. The private, nearly all-white, Morgan Academy, which is named after a former grand dragon of the KKK, did not admit a non-white member until 2008, after which a public frenzy ensued. The public schools are, however, over 90 percent black. The neighborhoods are segregated too.

“The whites will stay in one little area,” said Brandi Hatter, a 20-year-old who was born and raised in Selma. “There are different wards — you just live there and that’s the end of it.”

Based on the 2011 Alabama Kids Count Data Book, Dallas County is the worst place in the state for a child to grow up. The county ranks dead last among the state’s 67 counties when it comes to the well being of a child. Counties were measured in the areas of health, education, safety and security to determine their ranking.

Neo-Confederate groups still have a small but loud presence in Selma. Billboards like the one I saw, statues and flags serve as odes to racist heroes. On the weekend of Jubilee, the Alabama chapter of the KKK delivered 4,000 recruitment fliers to homes in Montgomery and Selma, some tied to rocks as a symbolic threat.

In a recent New York Times opinion piece, Selma state senator Hank Saunders and his wife, attorney and activist Faya Rose Toure, summed it up nicely: “Not only are the fruits (of the Civil Rights movement) scarce, but the roots are shallow and feeble. For the tens of thousands of African-Americans in Selma, life, as Langston Hughes said, ‘aint been no crystal stair.’ Better off is not equal.”

Enter the “Outside Agitators”

It was these discrepancies between what Selma is celebrated as — a town where the Civil Rights movement triumphed — and the current reality, that motivated my mom and stepdad to move to Selma. It wasn’t their idea: They followed their pastor, Mark Duke, and members of their church to Selma from Colorado seven years ago. The idea to move from the agricultural suburbs of Parker, Colo., to the deep south seemed like a crazy one at the time, but Duke said he was divinely inspired.

“Things of the spirit seem foolish to the flesh,” Duke often says, quoting scripture.

In 2006, the then Colorado pastor was visiting Selma for a civil rights history tour when he noticed that Selma felt “a bit too much like the 1950s.”

“While its one thing to play a confederate in a reenactment,” said Duke in an interview with The Intelligence Report, “It’s totally another thing to actually believe like one. There are some in Selma who still believe the South was right and that blacks were better off in slavery. They believe in maintaining segregation and celebrating the worst of the old southern transitions.”

In 2007 Duke brought small groups from Colorado with him to visit the south. Soon, about 50 people from his small church in Parker had signed on board to move to Selma with him.

When the group of mostly white Coloradans landed in Selma in 2007 — buying up Victorian homes with rocking chairs and almond trees, getting local jobs as school teachers and police officers — they really didn’t know what they were in for. The organization was immediately met with local skepticism. They were labeled everything from a cult, to troublemakers, “Outside Agitators,” “Nigger-lovers,” and “White Saviors.”

At first the resistance seemed connected to fear surrounding the church’s sudden arrival, its unorthodox structure (some members of their church share homes), and Duke himself.

Duke is a charismatic white man with a preacher’s charm and southern gentleman’s drawl. He preaches to stir. His fervent poetics would be appropriate for monumental crowds, but even when the audience is small, his zeal ignites. He is a voracious history nerd: Duke’s bookshelves are lined with biographies, historical novels and memoirs about war generals and civil rights leaders. One could wonder if his obsession with historical figures is pure admiration, or fuel for delusions of grandeur. Perhaps he’s hoping to make the history books himself one day. To the skeptical, Duke is a cult leader or false prophet. To the more supportive, however, he is just deeply passionate: about Selma, God and social change.

It was when Duke, his church and the Freedom Foundation (which is primarily made up of Duke’s church members), started challenging the status quo, that some of the town’s resistance turned ugly.

The most severe backlash occurred when a 5-year-old African American girl from their church, named Shania was admitted to the historically all-white, private Morgan Academy in 2008. At the time, Shania was the first African American ever admitted to the school, which opened in June of 1965 in response to the passing of the Voting Rights Act. The school is named after John Tyler Morgan, a confederate general, former grand dragon of the KKK, and six-term U.S. Senator who championed several bills to legalize the practice of vigilante murder as a means of preserving white power. The Academy has had a long held reputation for being a white domain.

When Shania was admitted, an angry board meeting followed. Then someone spray painted a mural picturing a young black girl (presumably Shania) hanging from a noose with the words “Freedom Fuckers” underneath. Duke’s son, Will, was badly bullied at the Academy. Duke’s house was vandalized, the grass spray-painted with the words: “Go Home.” A Facebook group was started called “Go Back to Colorado.” The church’s radio station, on which members spoke about Selma issues, was nearly forced off air when anonymous threats were issued to the station’s advertisers. A local pastor from another church hired a private investigator to research Duke and his group of Coloradans.

Then a vicious threat was posted on a message board:

“This farce, foolish ‘thing’ called Freedom Foundation is toying with explosive issues that Men of Action do not take lightly,” read the post. “Take notice. We will not wait for federal guns and federal gunpowder as was in Waco, Jonestown or Ruby Ridge. We do not turn the other cheek when striked [sic]. In fact it is best to strike first….Giants that were working or sleeping have been awakened. We will spend eternity in Hell if need be to protect our children and families.”

To this day, that message board has 17,617 comments. Duke said that the resistance was the group’s cost for promoting change.

“My family and the freedom foundation volunteers have paid the price, just as they [King’s foot soldiers] did 50 years ago,” said Duke during a rally speech in March. “We have paid the price because we too have stood up and agitated the status quo…we have stood up against those things that need to be looked at and changed. They [the volunteers] have had to endure lies and slander written online that are so ridiculous and hurtful that some of them I could not even repeat. They have endured hate and tactics that are behind the scenes; some tactics were used against Dr. King and his foot soldiers. The end goal is always to take leadership out.”

Jarah Botello, one of the original Colorado members to move to Selma, remembers the early days well.

“I was really timid and some of the persecution we faced here was challenging — people just hating me for no reason. Like not even knowing me and literally spitting at me or walking around me across the hall with a terrible look on their face, like ‘who are you?’ I had never faced anything like that,” said Botello.

Ultimately Duke and Botello think the pushback was fear: surrounding the foundations motives, and of change. Botello said the resistance, however, has only strengthened her resolve.

“All of that pushed out this fighter, or this advocate, in me that I don’t know would have ever come out if it wasn’t for the setting,” Botello said. “I think it cleaned out a lot of the timidity that was in me that was keeping me from really living fully.”

Birth of RatCo

One of Botello’s first jobs in Selma was as a theater and English teacher at one of Selma’s rougher public schools, Southside High School.

“It was kind of like Freedom Writers. Just the chaos in the school,” Botello said. “There’s a lot of hopelessness. We were on lockdowns a lot of days because there were so many fights.”

It was at Southside that Botello began formulating a plan to create the foundation’s youth theater company, Random Acts of Theater (RatCo for short).

“I had this idea that oh my gosh, theater can be so powerful, to empower children to speak and to find their voices,” she said.

Botello also thought it would be a good way to bridge the gap between the various schools and segregated wards within Selma. Botello partnered with her friend, church mate and co-director, Amanda Farnsworth. A few months later they were planning RatCo’s first production, Footloose. The play is about a young liberal from the big city who struggles to broaden the minds of a small town’s conservative establishment. The theme was appropriate.

Brandi Hatter, a Selma native, was 13 when she saw RatCo perform Footloose. She was incredibly impressed by the production, but was cautious about joining RatCo. She had heard rumors about the foundation and was taught by her New York-bred mother never to automatically trust anyone.

Still, she came back the next night and was welcomed backstage.

“They were like ‘you wanna come backstage and help us with props and stuff like that,’” Hatter remembers,. “They were bringing in a 13-year-old girl, scared of people, who knows nothing about theater, backstage to help with the show. They showed me love.”

Hatter kept coming back, but it took awhile for her to really warm up.

“It probably took me two or three years before I really trusted,” said Brandi. “There was a lot of hurt and mistrust in me, but I loved the atmosphere. I loved the fact that they were doing something fun, but also counseling students, and tutoring and feeding the people. It was really different.”

While these types of youth services — tutoring, service groups, counseling and after school programs — are common elsewhere, there was nothing like it at the time in Selma. Especially nothing that was open to all types. RatCo’s shows began attracting kids from a cross section of schools, even a few students from the 99 percent white Morgan Academy. Botello said this type of integration threatened some. Others still feared the church of outsiders was a cult.

Hatter’s mother came under attack for letting Brandi and her sister attend RatCo.

“People at work would judge her and say ‘you don’t know where your kids are and you’re a bad mom,” said Hatter. “But it was really cool to see my mom stand up and say ‘my girls are happier than they’ve ever been. Now she said that RatCo is the best thing that has ever happened to Selma.”

Much of the opposition and fear surrounding the foundation has subsided in the last eight years. Hatter said its because the foundation has proven that they’re in Selma to stay, not just “here for MLK weekend or Arbor Day or a small vacation.”

“They are really here to affect the city,” Hatter said.

Since its inception RatCo has put on 39 productions, plus 3 more in the works, and brought some of the RatCo kids on tour, to Montgomery, Ala., Washington D.C., Colorado and New York City to perform.

Traveling outside of Selma has become a goal for RatCo; not only to share the narratives of the real Selma, but also to open the eyes of the RatCo participants, many of which have never been outside the walls of Selma.

“They think Selma is normal,” said Botello. “It’s not.”

Bringing them outside the walls has expanded some of the kids visions of themselves and transformed what they believe is possible. Hatter, now 20, has moved out of Selma and is attending college to become a social worker. Hatter does, however, plan to come back to Selma after graduating, something she said is rare.

“A lot of people, if they have they chance to get out, don’t come back,” Hatter said. “But its hard to experience this [RatCo] and not want to come back. This is the most genuine, loving, environment almost anywhere that I’ve ever found.”

Birth of Students UNITE

Hatter is also the Outreach Coordinator for Students UNITE, the foundation’s student activist group. Students UNITE is made up of kids like Brandi, who grew up in RatCo and are now in college. Students UNITE’s birth, however, happened a bit by accident.

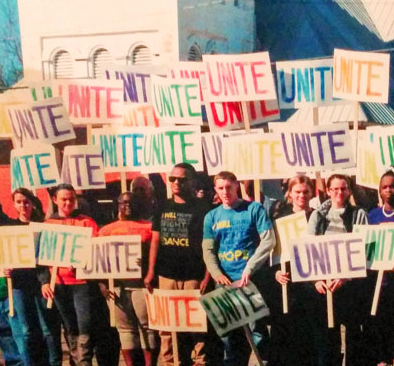

In the summer of 2009, a group of RatCo college students attending Samford Univerisy in Birmingham, dreamed up a wild idea to dance on the Edmund Pettus Bridge with a unified, diverse group of people from across Alabama. The idea was to give the historic bridge a new, more positive image; one that would promote a more integrated future for Selma.

Project: Dance grew quickly. Mayor George Evans agreed to shut down the bridge. The students spent 10 months teaching groups of people, of all ages and ethnicities, the dance. Local schools even forfeited their gym classes to let the dance be taught. Civil Rights foot soldiers from the 60s joined the group.

Ten days before the event, Evans addressed the dancing crowd at a rehearsal. He canceled Project: Dance. He had caved under the pressure of a faction of community members who did not want to see the integrated event go forward. Coincidentally, council seats had shifted earlier that month, seating Cecil Williamson, an “unrepentant neo-Confederate.”

“The kids were crushed,” said Amanda Farnsworth.

The event, however, also gave new weight to the Project: Dance mission.

“That event really gave them something to fight for,” said Botello. “It was obvious that they were not allowing us to dance on the bridge because we are unified. You can see footage of the mayor speaking to the kids — they were so upset. That opposition came at them personally, and it became more like they are dancing for a real reason.”

Hatter agrees. She said Project: Dance was fuel for her fire.

“I definitely felt more like an activist after it,” said Hatter. “It was really interesting to see that happen. You can feel something in your heart saying, oh my gosh, something is wrong here. Somebody really doesn’t want this to happen. And so that gave more evidence to the fact that it should happen.”

Since then, John Lewis, who co-led the historic Bloody Sunday march in 1965 when he was only 25, has come on board with Project: Dance, promising its organizers to one day help complete the project.

Lewis has been a huge inspiration to the leaders of Students UNITE. Lewis was only 12 the first time he was arrested for participating in a peaceful protest. He then became the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the most tumultuous times of the Civil Rights Movement. He participated in some of the Movement’s most vital moments to promote de-segregation. Students UNITE is somewhat modeled after Lewis’ SNCC.

Since Project: Dance, Students UNITE has gained momentum. This year, the group organized a campaign to re-name the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The petition, which was sponsored by change.Org, has gained close to 200,000 signatures. The group also planned a march during Jubilee weekend to the Confederate cemetery where a statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest resides. That protest had to be re-routed when a small group of neo-Confederates gathered at the statue in opposition. While there probably wouldn’t have been violence, Students UNITE leader John Gainey said he wants to be sure that the Students UNITE crew is heavily trained in King’s nonviolent tactics before they face real tension.

Nonviolence training has become one of the cornerstones of the Students UNITE mission. Although Gainey realizes that the term “nonviolence” is often misunderstood.

“People think it means no violence, as in a passive stance,” said Gainey.

Really nonviolence is about direct confrontation, but confrontation that is backed by agape (unconditional) love.

Gainey and members of Students UNITE now teach King’s nonviolent principals during the Freedom Foundation’s Alternative Spring Break (ASB) programs. Students from across the country visit the foundation during Spring Break to volunteer, learn about civil rights history and participate in nonviolence training.

“We place a huge emphasis on the learning component of the experience,” said Shawn Samuelson, director of the foundation’s ASB program. “We feel it is critical to understand the history, environment and culture in order to understand why Selma is the way it is today.”

Since the foundation started the ASB program in 2008, approximately 2,500 students have participated from 50 different schools across the country. The program has grown every year and saw exponential growth in 2011 when the foundation’s program was recognized as “Site of the Year” by Breakaway, an organization that helps connect colleges with ASB programs. This year alone, the foundation hosted 650 students.

In July, Students UNITE will host a Summer Nonviolence Training Institute specifically designed to teach King’s philosophies.

Having seen the wreckage caused by the recent Baltimore riots, Gainey said now is as important a time as ever to teach students about making change the right way.

A Young Revolution

Lynda Lowery, who was the youngest protester to march from Selma to Montgomery alongside Dr. King in 1965 (hear her full story here), agrees wholeheartedly. She said that being a part of the nonviolence movement saved her life; without it, she would have become a “very hateful and militant person.”

At the age of seven, Lowery’s mother died unable to get a blood transfusion from the all-white hospital. From 7 to 12, Lowery “hated white people more than they could ever hate her.” But when she was 12, she heard “a remarkable man speak.” It was Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

“He spoke about change and how you make change: through steady, loving, confrontation. I heard those three words and said, I could do that.,” remembered Lowery.”He said it again: Steady, loving, confrontation. It felt like a warm blanket on a cold night. I was convinced, at 13, that I could make change using steady, loving confrontation.”

Lowery started training in Dr. King’s nonviolent, direct action philosophy. She became involved with the Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee (SNCC). She marched with groups of her classmates, all in their teens. In the 1960s, she said, it was primarily “a children’s movement.”

“We the children went marching because if our parents did they could loose their jobs, or worse, the KKK would rise up” she explained. “It became a children’s movement so we could ease that burden from them.”

Even though today adults might not face the same degree of pushback for participating in social activism , Lowery said the movement still needs to be powered by youth. She has been a supporter of the foundation because, like the movement she was a part of, the foundation focuses on young people and nonviolence training. They subscribe to the notion that to make change, you need the energy of the young people, and the wisdom and leadership of the old.

In a sense, it seems the old and new movements are joining hands and trudging the bridge of change together.

“The new movement,” Botello said, “is fueled by a powerful exhibition of integration.”

Selma was, and is, a testing ground for change.

Or as a RatCo participant stated: “Maybe we can‘t change an entire nation right now, but we can start with a city. And if the city isn‘t ready for it, at least the change has started in me.”